Kombi Camera and Box

It can be surprising to learn that this tiny metal box camera, introduced in 1893, made important contributions to the development of modern photography.

Historic Firsts of The Kombi Camera and Graphoscope

The diminutive size and apparent simplicity of the Kombi may give the impression that this was a simple camera to operate — perhaps no more difficult than a Kodak camera of the same period. Nothing could be further from the truth. Although it is a well designed, ground-breaking camera for its day, the fact of its small size has a lot to do with its difficulty of use. An example of this, is that for the camera to be small, yet produce an image of acceptable quality, the maximum lens aperture was by necessity small. This small aperture meant that snapshot exposures could only succeed under the clearest and brightest lighting conditions. Although the Kombi was capable of taking instantaneous exposures, time exposures were the recommended mode of operation.

Alfred C. Kemper of Chicago, Illinois was the manufacturer of the Kombi. William V. Esmond of Chicago was the inventor. The Kombi patent was applied-for and granted in 1892. William Esmond assigned Alfred Kemper one half of the patent rights. Here is a link to the Kombi patent

The camera body, measuring approximately 1 3/4 x 1 3/4 x 2 1/8 inches, is made entirely of brass with an oxidized finish. The oxidation decorated the body with attractive diagonal stripes. By the way, it is best not to clean the Kombi's exterior. This usually results in destroying the decorative oxidation.

The Kombi was a successful camera, well received when introduced, and it is said to have been sold in very large numbers. Yet it is an excellent example of how difficult it was to practice photography as an amateur in the early roll-film period. This difficulty, but also the historical significance of the Kombi, is what I hope to convey in the remainder of this article.

In the Kombi's day there were only two manufacturers of roll film: Eastman Kodak and Blair Camera Company. Eastman Kodak was the dominant leader in the roll film field and had the financial resources, if it desired, to risk making a non-standard film size for an untested camera design. The Kombi required a roll film many times smaller than any produced by Kodak.

Fortunately for collectors of this interesting and important miniature camera, Eastman Kodak Company agreed to manufacture the tiny Kombi roll film. If Kodak had not agreed, I doubt this camera would have made it to market.

I think the fact that Kodak made this agreement indicates that George Eastman was at the very least, curious to see if a miniature camera could be a commercial success. Two years later, in 1895, Kodak introduced its own miniature camera, the Pocket Kodak. The first Pocket Kodak cameras were roughly the size of the Kombi, but created a 1 1/2 x 2 inch image compared to the Kombi's 1 1/8 inch square format. The larger image size of the Pocket Kodak, although it may not seem that much larger than the Kombi's, allowed the Pocket Kodak to produce higher quality images with instantaneous capability in a miniature camera.

This view shows the Kombi with its elaborately engraved front. The lens of the Kombi serves two functions. It is the camera taking lens and the eyepiece of the graphoscope, or viewer. The name Kombi was chosen to emphasize that the taking and viewing of photographs were combined in one instrument.

Using the camera body and lens as a viewer was a clever idea. Variations of this concept were offered over the years by a few other manufacturers, but they did not take hold in the marketplace. A few years before the Kombi's introduction, E. & H. T. Anthony was offering for sale a combination camera and lantern slide projector. In 1904 Jules Richard of Paris, France introduced the Glyphoscope, a stereo camera that like the Kombi, could be used to take and view photographs. Now modern digital cameras, with their built-in viewing capability, have revived the century-old Kombi design.

The dial seen at the top center of the camera is used to arm the shutter. It can be set to two positions. A curved piece of metal with two notches can be seen at the top of the camera. These notches latch the arming dial in place. The center position is used for time exposures. The farthest position sets the shutter for instantaneous exposures. The shutter release, a spring lever, is located on top of the camera. Pressing the lever releases the dial from the notched latch, activating the shutter.

Before arming the shutter, it was important to remember to cover the lens with your finger. This is because the very simple shutter was not self-capping. It was not uncommon for early shutters of the day to require capping before arming. But it was important to remember this, or a ruined exposure would be the result.

Note that the Kombi does not have a viewfinder, and an accessory viewfinder attachment was not offered for sale by A. C. Kemper. I imagine this was not a good thing.

The camera back reveals a round, removable cover plate. The plate is removed to use the camera as a graphoscope, or positive transparency viewer. Photographs taken with the Kombi could be processed as prints, or positive transparencies in roll form. To view transparencies, the roll was reinserted in the camera, the back cover plate removed and the camera back was held to the light. The camera lens, now acting as the viewing lens was held to the eye. The film wind knobs were used to position the individual photographs for viewing.

An unusual feature of the Kombi roll holder is that it has two wind knobs. I don't know of another roll film camera with two wind knobs, as one is considered sufficient. The addition of a second knob had to increase the cost of producing the Kombi. I think one reason the camera was designed with two knobs was to allow transparencies to be rolled back and forth when the camera was used as a viewer. Otherwise, it would not be possible to back up and view a previous image without reloading the roll. A second reason, I believe, was that because the roll film did not have a core or spool, and this strip of film needed to be tediously wound onto a roller in a darkroom, the second wind knob was used to simplify loading, and to set the correct film tension.

The strip of brass, seen running the length of the camera was called the Kombi Clasp in A. C. Kemper literature. This was an accessory sold separately from the camera, priced at 10 cents. The word Loaded is stamped into the clasp. Presumably after loading fresh film into the camera the user clipped the clasp into place to serve as a reminder not to open the camera and expose the film. The fit and precision of the Kombi body is so perfect that the clasp is not necessary for, nor was it intended to be used, to hold the roll-holder to the camera body.

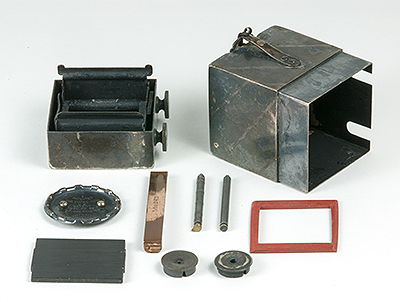

This image shows the Kombi separated from its roll holder and the holder disassembled. The round rods in the center are the film rollers. The black plate, bottom left, is the platen. The platen holds the film flat. The reddish frame, bottom right, is the mat. The mat defines the image frame, or borders. This mat creates an image approximately 1 1/8 inches square. A mat for producing round images was also available. I am not certain if both mats were provided with the camera, or if the round mat needed to be purchased separately. But the Kombi catalog does list the round mat as being available for 20 cents.

Also shown are the brass clasp and two "caps". The caps, as Kemper called these items, are lens apertures, not what we would think of as lens dust caps. The caps had different size openings, to be chosen according to light level and type of exposure. A cap is mounted on the camera simply by pressing it onto the lens barrel. The cap with the smaller opening was used for time exposures. The cap with the larger opening was used for snapshots in very bright light. When taking snapshots in normal daylight, the lens was used without a cap. It seems the reverse of usual practice to use a smaller aperture for low light levels and time exposures, but from a reading of the Kombi instruction manual, I think I understand the reason.

Kemper recommended that beginners make time exposures instead of snapshots, saying it would be easier to achieve good results in any lighting condition. The Kombi manual provides a Time Table - a very elaborate guide to choosing exposure times under a variety of situations. If I were using the Kombi today, I would need to keep this table with the camera, as I doubt I could memorize all the possibilities. As it was recommended to make time exposures with the Kombi, I think the reason the small aperture was used, was to reduce the light reaching the film so that reasonable exposure times in seconds could accommodate all lighting situations. The Time Table recommends using one second for bright light and 50 seconds and beyond for scenes in dim light. Obviously it is recommended that time exposures be made using a tripod or other support.

Three options were available for film processing. The easiest route was to mail the entire camera to the company, enclose payment and eight cents for return postage, and await its return. All Kombis have a serial number stamped both on the body and the roll holder. You were advised to write down the number when sending the camera, apparently to assure Kemper returned cameras and pictures to the correct owners. Kemper reloaded the camera with fresh film prior to its return.

A second means of getting your film processed was similar, but involved only mailing in the roll-holder. This was a brilliant concept, though I don't know how popular it was. The idea was you could purchase a second magazine, as Kemper called its roll-holder. While your film was processed you could continue taking photographs.

This was the first time an interchangeable roll-holder, magazine, or interchangeable back, depending upon your choice of words, was offered for a roll-film camera. (The earlier Eastman-Walker roll-holder was sold as an accessory to be used on glass plate cameras.) Years later various manufacturers would offer this feature on high-end and professional quality cameras.

My copy of the Kombi instruction manual lists the price of the complete camera at $3.50. A roll of film for 25 exposures cost 25 cents. A second magazine, loaded with film cost $1.50.

The final and most difficult way to process your film, would be to do it yourself. Kemper attempted to simplify the process by offering complete outfits and detailed instructions for this endeavor. But the real difficulty in taking the do-it-yourself route lay in learning to reload the camera with fresh film.

To do this, the roll-holder was taken apart. Then, in the dark, it was necessary to trim the end of the film with scissors so it would fit the roller slot. There are two rollers, and they are not exactly identical. It was important to start the film on the correct roller. The film was wound onto the first roller, then the tail of the film was trimmed to fit the second roller. Next the rollers with film attached were inserted into the holder. This is not a trivial operation in daylight and I am sure it was much more difficult in the dark. Then, somehow, still in the dark, the platen was slid into the holder behind the expanse of film, and the mat was slid in front of the film. If all proceeded well, the last step was to fit the holder to the camera body.

The reason the two film rollers are not identical is that one has a small protrusion called a click pin on one end. As film is wound through the camera, the click pin revolves, striking a click spring with each revolution. This action creates a clicking sound, and it is this sound that tells how far to wind the film for the next exposure. The roller was to be wound until 3 clicks were heard. This system seems workable, as far as it goes. But what is missing is a way to count exposures. I would have trouble remembering how many shots I'd taken on a twenty five exposure roll of film. The camera did not use a red window for indicating exposures, nor did it have an exposure counter.

I explored the workings of the Kombi camera in great detail hoping to convey a sense of what it was like to work with a simple, compact, early roll film camera of over a century ago. In addition, I think that the Kombi deserves merit for innovations that helped to modernize the photographic process.

The Kombi's primary innovation was its precision all-metal body. The Kombi was not the first all-metal camera, but it was the first roll film camera made entirely of metal. Roll film ushered in the modern photographic age as it greatly simplified the work of taking a picture. As films improved, image sizes shrank and cameras could be made more compact. Manufacturers found that metal could deliver the precision required of miniaturization.

Proof that the Kombi was not simply a toy or novelty camera can be seen in the precision of its roll-holder. The Kombi has a solid feel in the hand. Its controls work smoothly and fit is impeccable. I think it is obvious that the Kombi was well made.

The Kombi roll-holder was not the first interchangeable roll-holder to appear on the market. In 1885, George Eastman and William Walker introduced the Eastman-Walker roll-holder accessory for glass plate cameras. In contrast, the Kombi magazine was designed as an integral but interchangeable component of the camera. Decades later manufacturers would refer to this type of packaging as a camera "system".

This level of interchangeability was in large measure due to the Kombi's metal construction. It was not practical to build miniature scale wood-bodied cameras with the tolerances required to achieve full interchangeability of components.

As with many innovative products, the Kombi may have been a bit ahead of its time. I say this, because it was not easy to take a good quality photograph with the camera. Partly this had to do with the state of the art in film emulsions. I also think that in order to launch a metal-bodied miniature camera at an affordable price, certain features were left out. Among the most important were a way of counting exposures, and a viewfinder.

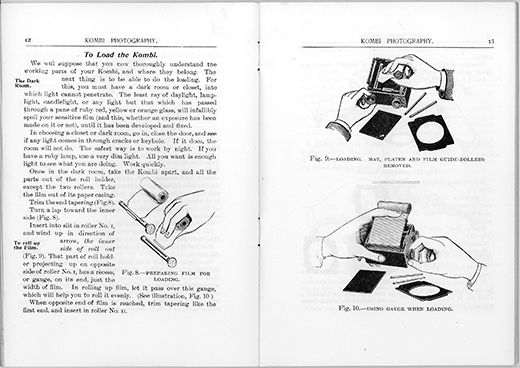

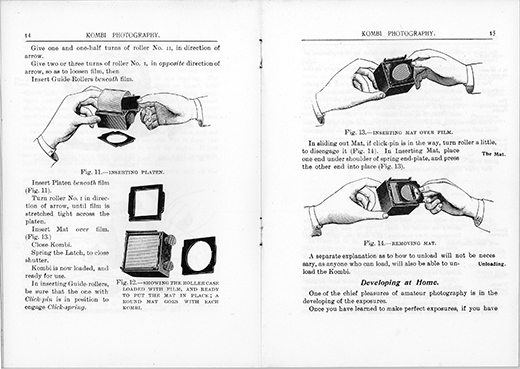

Although the text is not legible in these scans of the Kombi instruction manual, the drawings of the steps required to load film in the camera convey how difficult this must have been to carry out in the dark.

|

Page created February 21. 2002;

updated December 20, 2020 |